How the food industry hacks us for profit

Often, despite our best intentions, we find ourselves eating food that we know isn’t healthy, and eating far too much of it, too. So if our brains can tell us that what we’re eating is bad, why don’t we listen?

The answer is a complex interplay between human wiring and clever industry tricks that take advantage of human nature to sell more products. But forewarned is forearmed - by learning some of these tricks, you’ll be better able to avoid them.

We’re wired via dopamine to seek pleasure

Dopamine is sometimes called “the pleasure hormone” because we experience a deep satisfaction and pleasure from it. It’s released in conjunction with events that tend to boost our personal or species-level survival chances, the most common ones being food, shelter and relationships with others.

In our hunter-gatherer prehistory, our diets consisted of whatever was available at the time. Food was usually scarce. Life tended to be tough, and short. But in the modern world food is no longer scarce, but abundant — we are constantly surrounded by food options. This cultural and societal shift, a meteoric rise in food availability, happened so quickly that our bodies haven’t adapted to it, and our fundamental wiring continues to work as if food was still scarce. Our caveman brains and bodies are nudging us to take whatever is available right now, because we don’t know when the next meal might be.

We’re being hacked

“Hacking” as a term started with a positive meaning: early computer programmers had very limited, constraining systems to work with, so they had to be ingenious and create clever workarounds, to make useful software. Over time, as humans became reliant on IT systems, a new connotation emerged, hacking as unauthorised access that break the rules, to make money — a security breach to steal data, for example.

This negative meaning applies well to a number of industries, who “hack” the human wiring in order to pursue a business objective — more sales, repeat business and so on. Tobacco companies hacked us by adding chemicals to cigarettes to increase how addictive they were. Advertisers hacked us by exploiting our vanity, and hiring Hollywood stars to push products, so we’d buy the product to “be more like them.” And social media networks hack us by showing content that is inflammatory or enraging, to grab and keep our attention — no matter how toxic the result at a psychological or societal level.

Large food manufacturers are also hackers. They are well aware of this human tendency — our ancient, still-a-caveman wiring — to eat what we can right now. And they lean into it. By loading products with disastrously high levels of carbohydrates, sugar, fat and salt, they are hacking our pleasure wiring and juicing their near-term sales, but incrementally destroying the long-term health of the people eating the foods.

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are addictive

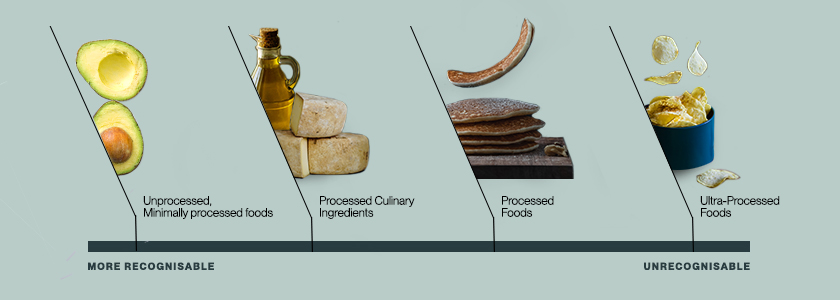

The Food & Agriculture Organization (FAO) classifies foods into 4 categories:

- Unprocessed and minimally processed foods - e.g. fresh fruit and veg, plain meat, eggs and mushrooms

- Processed culinary ingredients - e.g. cheese, oils and salt

- Processed foods - e.g. tinned tomatoes, cooked ham and fresh-baked bread

- Ultra-processed foods - these are the ready meals, boxed cakes, confectionery, crisps and other packet food. As a rule, these foods tend to be higher in fat, salt or sugar than unprocessed foods, and contain more ingredients

Less-processed foods look more like themselves — the more something is processed, the less recognisable it becomes

Less-processed foods look more like themselves — the more something is processed, the less recognisable it becomes

As a general rule, UPFs tend to be high in simple carbs and sugars, high in chemical additives (artificial colours, flavours, preservatives and texturisers, for example), and low on fibre, vitamins and minerals. This type of food tends to trigger a strong dopamine response, which can lead us to overeat now, and then to crave the same highs in the future.

Eating begins with the eyes….and the nose….and the ears

We are attracted to bright colours - and food manufacturers know it. That’s why ultra-processed foods tend to come in red, yellow and orange packaging, to draw our eyes and stimulate the appetite.

Food sellers also know the power of aroma. Fresh baked bread and pies, freshly brewed coffee, just-popped warm popcorn - these are all powerful, evocative scents that appeal directly to the senses.

As for the ears - notice the sounds in food adverts (either real or suggested) and you’ll notice sizzling meats and cool, inviting soft drinks poured generously over ice. Again, these sounds are carefully created to tempt you, bypassing your logical mind and heading straight for the senses.

7 common tricks to watch out for

“Eye level is buy level”

Supermarkets display the products they want to sell most of at eye level - these are often the premium brands. Lower-cost items are often tucked away at the bottom.

Buy more, pay less

Special offers, ‘buy two get one free’, exclusive prices ‘this week only’ - they’re all designed to make us buy more than we planned to.

Alluring words

Food packaging today is much more sophisticated -and complex- than it used to be. Actual nutritional values and ingredients are tucked away in the small print, while large, colourful call-outs lure us with words calculated to associate the product with health - even if the product as a whole is full of junk. Just because something is marked organic, vegan, high in fibre, or fortified with vitamins and minerals, doesn’t mean it’s healthy!

No added sugar

Check the actual proportion of sugars in the ingredients - and don’t forget to multiply the figure for 100g or 100ml up to the full portion size.

Low fat

Reducing the amount of fat in a food product will generally lower the calorie value, but it doesn’t always - and it isn’t usually any healthier either. And to keep the product palatable, manufacturers often replace the fat with sugars and artificial flavours.

Confusing portion sizes

The packaging says, “Only xxx calories per serving!” But there are 3 pieces in the box, and it says “serves 2”. The fat, carbs and sugars are listed per 100g. This is all done on purpose to confuse you into eating more than you wanted or to be able to post lower calorie information per serving, knowing full well that typically a consumer would eat all of the contents.

The suggestion of luxury

Without changing many (or sometimes any!) ingredients, a cheap-and-cheerful pasta sauce can be re-packaged to become an authentic, artisan Italian experience at three times the price. It’s still ultra-processed, but now it somehow sounds much more wholesome.